A recent investigation by the Inspectorate of Government (IGG) has revealed that more than 35% of public servants in Uganda paid bribes to secure employment, raising serious questions about meritocracy and public service quality.

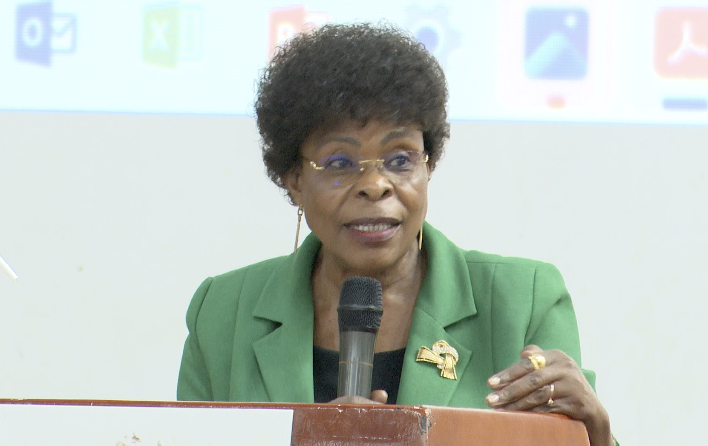

According to IGG Beti Kamya, many of those recruited through corruption may not have been the most qualified or suitable candidates.

“Somebody showed us they went to the bank or their SACCO and borrowed Shs 30 to 40 million just to pay for a job,” Kamya said. “And they do it because they know as district engineers, for example, they can recover that money from just one contract.”

The findings emerged from a comprehensive study into financial and social impacts of corruption in Uganda’s District Service Commissions. The investigation showed that job seekers were asked for Shs 78 billion in bribes, of which Shs 29 billion was paid.

Manifesting as bribery, nepotism, embezzlement, and other illicit financial flows, corruption continues to undermine public service delivery and drains government resources. The IGG estimates that Uganda loses Shs 10 trillion annually due to corruption, leading to poor infrastructure, delayed projects, low investments, weak social services, and even loss of life.

The education sector was singled out as the hardest hit, accounting for Shs 36.9 billion of the bribes.

Entry-level jobs in 20 surveyed districts required bribes averaging Shs 3 million, while senior positions demanded between Shs 40–50 million.

The shortlisting stage of recruitment was identified as particularly opaque and vulnerable.

“If they are not qualified and they bought the jobs, should we really be surprised when new school buildings collapse or show cracks just months after construction?” Kamya asked.

Over the past three years, more than 400 public officers have been dismissed for obtaining jobs through bribery or forged documents.

“Of those, 276 officers were interdicted and referred to their respective District Service Commissions for disciplinary action,” Kamya revealed.

Despite these actions, the culture of silence around recruitment corruption persists. Ben Kumumanya, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Local Government, urged citizens to break the cycle.

“People give money, keep quiet, and everyone pretends nothing happened. Today, what we take home is this: Let people speak out,” he said.

Political interference remains a major driver, with some district leaders allegedly using recruitment to reward allies. Herbert Otim, Chairperson of the District Service Commission in Kapelebyong, pointed out the pivotal role of Chief Administrative Officers (CAOs) in the process.

“The CAO controls the budget, can remove you from the payroll, or even deny you transport. That’s a powerful office, and not easy to talk about but it’s central to this problem,” Otim said.